How the Nazis invented German wine culture. A historical guest ramble by Peter Jakob

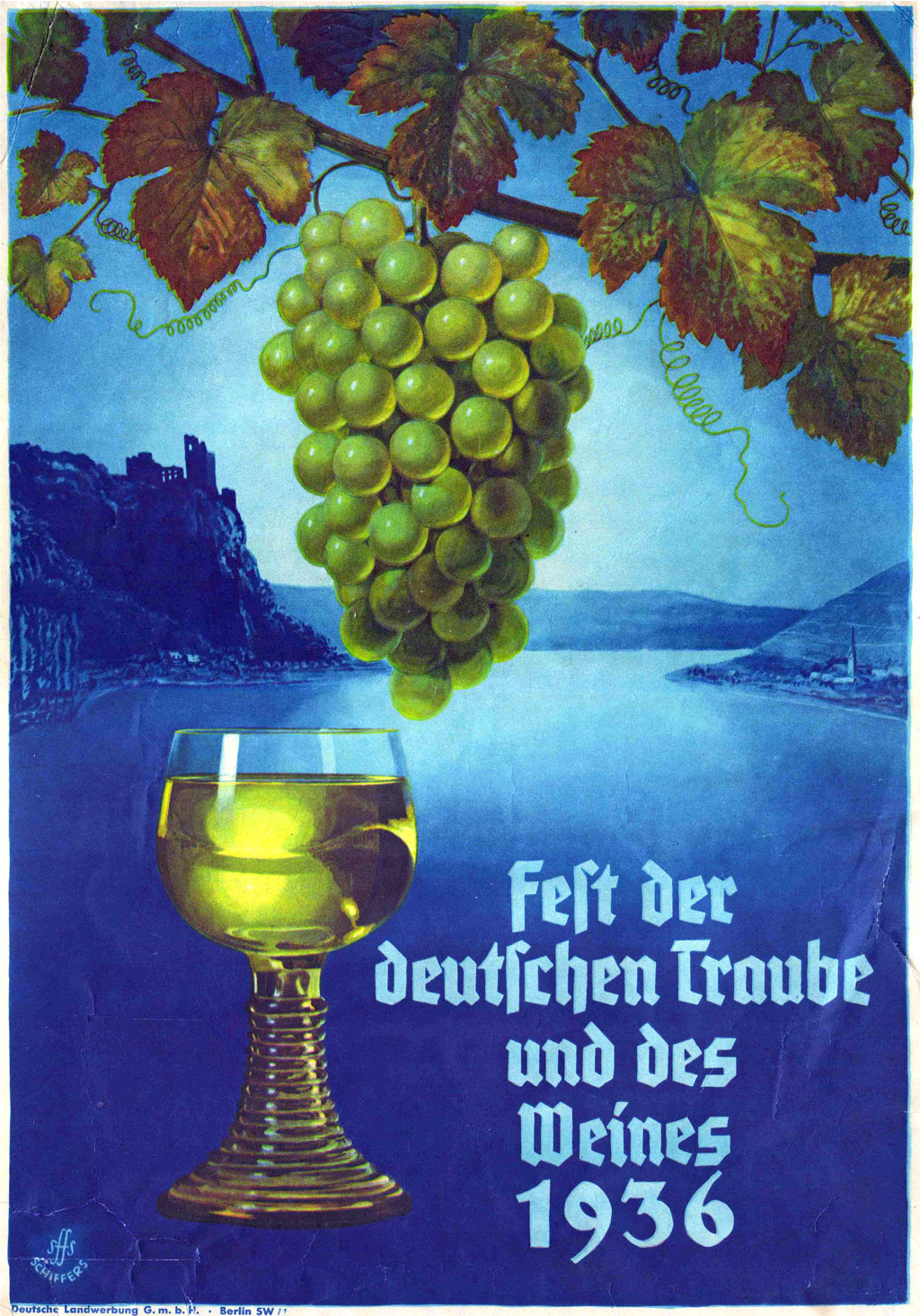

What could be more idyllic, more innocent than enjoying a glass of wine with friends at a historic wine festival? At least as far as Germany is concerned, the history of wine festivals is not always as innocent as one might expect though. In our latest Guest Ramble, wine blogger and historian Peter Jakob, aka MarcoDatini looks into the Nazis' attempt to invent a national German wine tradition through the creation of the Festival of German Grape and Wine / Fest der deutschen Traube und des Weines. A highly recommended read (also available in German), especially as it approaches the topic of wine with a critical, historical perspective that is highly unusual in wine blogging. Enjoy, and learn.

Das Fest der deutschen Traube und des Weines - how the Nazis invented German wine culture. A historical guest ramble by Peter Jakob

Asking people who lived through the Third Reich about the Fest der deutschen Traube und des Weines (Festival of German Grape and Wine) is likely to, after a moment of thought, evoke vivid memories. As wine festivals are fairly common today this may seem a little surprising, especially as many wine-growing villages and towns have made them a permanent part of the public calendar. While some of these local festivals may leave a lasting impression, this can hardly be said for many festival in larger cities. In the 1930s, it would seem, this was quite different.

Recent historical research on wine festivals has shown that these events had never been part of the traditional calendar of folk festivals, unlike, for example, the ubiquitous harvest festivals. They cannot be shown to have existed before the last decades of the 19th century, and even then there was no more than a handful of them. Only in the 1950s, the early years of the Federal Republic, did such festivals establish themselves widely as tourist attractions and agricultural and commercial fairs. However, these have been and are regional events, regionally sponsored and organised, while the Festival of German Grape and Wine took place, memorably so, on a national stage. (For wine festival culture see Herbert Schwedt: Wein und Festkultur im 20. Jahrhundert.)

Before turning to that moment itself, let's take a quick look at the situation that German wineries and wine growers found themselves in in the first half of the 20th century. The 19th century and the first years of the 20th were a golden era for German wine, with Rieslings from top estates among the most sought-after, prestigious and expensive wines in the world, and with the rank-and-file doing handsomely enough in their wake.

Rhenish wine growers in traditional costume, 1930. German Federal Archive, Bild 102-10150, licensed CC 3.0

This was not to last. The export markets lost during the Great War turned out to be lost permanently. Among the millions of dead claimed by the Great War were entire families of vintners. During the war, vineyards lay waste, and in the postwar years there was a lack of workmen, dead or crippled as they were, able to pull businesses back out of decline. The hyperinflation of the early 1920s brought enormous economic turmoil, leaving many wineries in crushing debt. The only massive protest movement of wine growers ever recorded in German history took place 1926 along the Moselle. With the onset of the Great Depression in 1929, things took another turn for the worse.

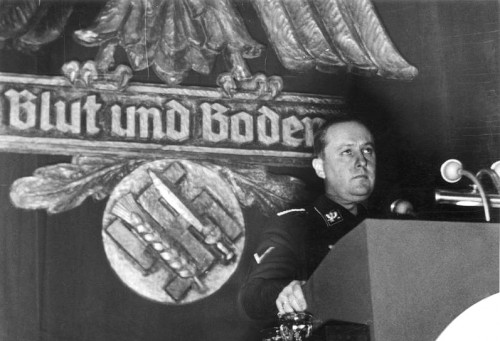

The Nazis, however, saw winemaking in a different context. A focus on agriculture and the idea of the farming community as a backbone of the nation, the so called Bauerntum, was an important aspect of Nazi ideology. Agriculture was brought under the control of the party (Gleichschaltung), with the so called Reichsnährstand (RNS, roughly translating to 'Imperial Agricultural Estate') formed as the the most powerful organisation. Bauernführer, 'farmers leaders', were appointed on all levels, from regional to the Reichsbauernführer ('Imperial Farmers' Leader'). Adam Tooze's book The Wages of Destruction has a good overview of this process.

Reichsnährstand plaque in typical monumental style. Photo by N. Lange, licensed CC BY-SA 3.0

The unusually hot and dry year 1934 brought just the emergency needed to take the process one step further: While it was a catastrophic season for German agriculture as a whole, wine growers saw their yields rise dramatically. Instead of the average production of 220 million litres of wine, wineries produced more than twice that amount, about 470 million litres. The massive over-production soon created problems of its own: for sheer lack of demand, cellars were still crammed full in 1935. This caused serious concern: how should wineries store the next incoming vintage?

This is where the National Socialist organisation and propaganda machine came into play. A plan for a nationwide campaign to increase sales of German wine was developed. Lead by the RNS, and working with local and national NS organisations (such as Deutsche Arbeitsfront, NSG Kraft durch Freude, Gaupropagandaleitungen etc.), the Ministry for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda proclaimed a week long Fest der deutschen Traube und des Weines. The idea was to encourage the people to consume wine (as well as sparkling wine and table grapes) and thus help the wineries to reduce their stocks.

The Festival was a construction of the NS regime and had no historical precedent. In order to market the culture of wine as part of their 'blood and soil' ideology, the National Socialists invented a tradition that had not existed before. The festivals were meant to reflect a certain type of 'Rhine romance', influenced by vine imagery, the folklore of various wine regions, and an idealised German wine culture rooted in the Romantic movement, the genre paintings of the 19th century, but not in reality. What was such a festival like and how was it organised?

The basic organising principle was twinning cities with wine growing villages. Smaller cities were twinned with one or two villages, larger ones with several. Berlin for instance was twinned with Mehring, Zeltingen, Winkel, Oppenheim, Hambach and Duchroth, whereas Dortmund twinned Pommern, Mertesdorf, Bodenheim and Weisenheim-Sand. Apart from a range of activities involving local restaurants or societies, larger, centrally organised events were planned. The twinning festival in Berlin included the following highlights:

- Gala concert,

- general ball,

- welcome address by a speaker,

- introduction and performance of the Moselaners,

- performances by important artists,

- acrobatic performances,

- tombola (distribution of wine vouchers, to be handed out after leaving the pub).

The Festival was controlled tightly by the Reichsnährstand. Prices were regulated. From the decoration of the windows up to the details of a massive propaganda campaign that made use of all available media, the festival was centrally planned and scripted.

It may come as no surprise that the regulations also included an Arierparagraph (Aryan paragraph). Participating wine shops had to prove that all staff were of 'Aryan blood'. This made anti-Semitism, albeit somewhat hidden from the public, an inherent part of the Festival of German Grape and Wine.

Apart from this aspect of the NS-ideology some of the other typical elements of the ideology of the early years of National Socialism were on display: Still firmly rooted in social revolutionary ideas of the NSDAP, yet with noticeable distance from the political Left, the Gauwirtschaftsberater (an economic advisor) for Koblenz-Trier took great pains to emphasise that the idea of 'wine as a drink for the fat cats' (Bonzengetränk) was a Marxist one. Vinters were described as the 'strongest bulwark of Germanness'. This clearly shows the idea of Volksgemeinschaft, the national community, but also the idea of Blut und Boden (blood and soil) of the agrarian faction within the Nazi party.

Reichsbauernführer Walter Darré in 1937. Photo from German Federal Archive, licensed CC BY-SA 3.0

In the same way, the Gauwirtschaftsberater's request to 'civil servants and the permanently employed with medium or higher income' to build up private German wine cellars is rhetorically influenced by the ideology of Volksgemeinschaft. A similar argument can be found in the general explanation given for the Festival's creation: It was said to not simply be set up for economic reasons, but specifically 'to mitigate the great hardship of the German Vintner Class, our ethnic brothers in the western borderlands'. Typical of the language of National Socialism this was designated as 'Socialism of Action'. The festival was meant to weld together in practice what Nazi ideology kept proclaiming in theory: the nation as an organic community tightly bound by a dramatic common destiny.

The festival of 1935 turned out to be a big success and was repeated in 1936. As 1936 was not a a year of record harvests, the 1937 celebrations were shortened to two days. In 1938 the harvest was not good enough, so there was no reason to hold any at all. The planning for the festival of 1939 had started early, but never got off the ground as the outbreak of war was all too clearly on the horizon.

The larger question brought up by this story, and it is one of some relevance to German wine folklore as it is today, is whether the Fest der deutschen Traube und des Weines had an impact on the wine culture of the German Federal Republic that succeeded the Nazi state. Almost all the well known German wine festivals were set up in the 1950s and the following decades. Was the Fest der deutschen Traube und des Weines an inspiration for those festivals, purged of the more heinous aspects of ideology, but heir to falsely folkloristic aesthetics aimed to increase the consumption of wine

Wine procession, around 1960. Photo by jessica @ flickr, licensed CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

I would like to thank the City Archive Herne for kindly giving permission to use the Festival poster for this article, as well as the City Archive Lünen with its extensive records on the Fest der deutschen Traube und des Weines. Translation of Peter's original German text by the Wine Rambler.

Those of you who read German

Those of you who read German might be interested in the comments section of the German version of Peter's article, where you will find further references and a few additional thoughts from Peter.

Can't wait for more of this

It's nice to come home from a bavarian lake holiday ... and find the launch of the Wine Rambler's history section completed, so a great many thanks, however belated, to Peter for sharing his research and his insights. I cannot disagree with Randall Grahm calling it a "fascinating read", and what's maybe more important, "a moment of reflection".